Points of crisis can usefully reveal contradictions and opportunities for organizing. Crisis can also shut us down and make it hard to connect, think, and act. The mobilization of the right-wing anti-mandate crew in Ottawa and elsewhere in Canada is one such crisis. Direct confrontation with the far right is important and can be effective, but in the present moment in Ottawa it’s complicated to mobilize in that way. The most common responses to this complexity that we’ve seen are: 1) Calls to intensify policing and bring in the military; 2) Calls to get people out in the streets to fight the right immediately; 3) Calls for dialogue, understanding, and to wait out the demonstrations. This last one is a real minority, especially among the people most directly affected by the convoy’s behaviour and ideology.

We think none of these are adequate ways to approach what’s happening here. This moment is an opportunity for us to welcome large numbers of recently politicized people into a movement for transformation, build care for each other and autonomous organizing while fighting authoritarianism, and refuse to intensify the state’s carceral capacity,

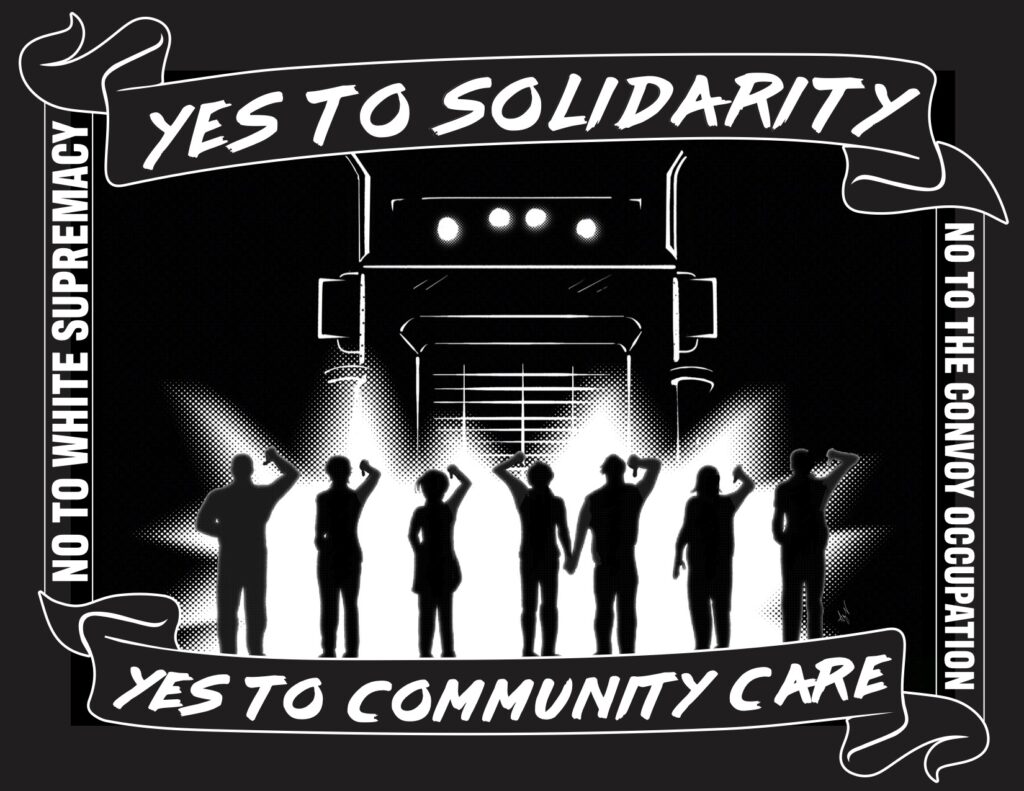

In Ottawa, so far there have been substantial community-generated attempts to take care of one another; these are the seeds of collective mutual aid projects and we celebrate them. Every person who receives a loan of noise-cancelling headphones, whose pets have a quiet place to stay to escape the endless honking outside their house, or who has help to get groceries or to their job is someone whose survival and flourishing anyone on the left should care about. These kinds of mutual support efforts are awesome, and they show that always it is ordinary people, not the state, who can meaningfully care for one another. There has also been some collective counter-protesting and group walks around the areas affected by the right-wing demonstrators.

These approaches will likely not be enough to get the authoritarian occupiers out of the streets now or oppose fascist collective organizing in the future. And it is far better to prevent right-wing adventures in ruining our lives than to clean up the aftermath. But since we’re in the middle of having failed to prevent an occupation of our city, there are a few things that are helping us orient as anarchists committed to collective liberation. We don’t have any answers or correct lines here, so we’re sharing these thoughts in the hopes that they might help with thinking about both the present and the long haul. And we’re excited to work with other groups in building true freedom in Ottawa, for everyone.

Obvious starting point: Everyone is really tapped out and tired right now. These last years have been ridiculously hard, but the bad has been distributed to hit parents, racialized people, disabled people, people living in poverty, and imprisoned people hardest and worst. Covid has been a hard time to organize in, and so aside from us all being individually depleted we’re collectively functioning below strength. Simply enjoining people to get out and organize isn’t going to solve these facts about our real capacity.

The good news: we have never seen so many people in Ottawa overtly disgusted with authoritarianism under the sign of the Canadian flag, or so many people ready to condemn racist politics. This means that there are a lot of people very new to protests and organizing who want to get involved. Many of them are jumping in wholeheartedly. This is great! And also many of them have never done any collective organizing at all, and may not have a lot of political education, so they tend to revert to the forms they know, including setting up hierarchical and bureaucratic formations in the actions they’re supporting.

How we welcome new activists “in” to ongoing movements matter, and how we nourish people who’ve been around for a while matters too. We would do well to be generous and compassionate with everyone who is orienting against the convoy – that includes very new organizers whose impulse is to call the cops, liberals who are just beginning to wonder if calm argument is the right approach to fascists, and jaded former activists who are dipping a toe back into organizing spaces. We’ll all make mistakes, so this might be a space where we adopt the practice of calling in rather than calling out problems. Instead of feeling demoralized or cynical, let’s start with: It’s great that we have the chance to bring a lot of people into organizing against authoritarianism right now! How can we do that in a way that builds our collective power and demonstrates how fun and meaningful it is to be in this together?

As always, how we do things is how we do things. Those of us who’ve been organizing for a while know that mass mobilizations are always disruptive – the problem with the convoy is that the content of their disruption is racist, sexist, authoritarian, and hurts people. We on the left want to build disruptions that are welcoming and nourishing to everyone. And this is a long game – we should be treating one another as though we’ll be in movement and community together for a long, long time. No one is disposable. We want to build long-term movements that are rigorously kind to people and hard on problems.

And this is only one of the reasons that calling for intensified police or military intervention, or otherwise giving more power to the state is not the solution to authoritarianism. As many have pointed out, the Ottawa Police Services have accorded a stupefying level of courtesy to convoy participants, actively participating in creating a context where they are safe to party, build huts, take saunas, and honk their horns at torturous levels for days now. Their behavior is an expression of the ways policing is always in service of white supremacy. It is in part the individual white convoy members they are protecting, and it is also that the convoy is part of a broader eugenicist, overtly white supremacist tendency. The contrasting harshness with which OPS treats movements for Black and Indigenous liberation, or the ways they brutalize and murder racialized individuals in our city, comes out of both individual racism and racist policing structures. We cannot police our way out of authoritarianism because policing is inherently authoritarian.

All of us on the left in the Canadian context find ourselves in a “three-way fight” situation. This is when we oppose the far right (in this case, associated with the convoy) and also we oppose the people they oppose (the Canadian state). Although the convoy participants are our enemies, they are just one expression of the far deeper structural and systemic problems we all confront. We desperately need to fight the right in all of the places they’re mobilizing. And as we fight the convoys across the country, it’s worth asking ourselves how the fights we take on in these specific contexts can build that bigger movement.

This current confrontation with the anti-mandate crew is just the latest iteration in a long fight that we’re still in the middle of. We here in Ottawa, like others across the globe, have been fighting authoritarianism and fascism for a long time now. In Ontario this has included diminishing the power of the Heritage Front, fighting white supremacists on the lawn of Parliament, and taking on rural white power organizing. This convoy is the most significant upsurge of overt white supremacism in our country in a while, but we’ve confronted them before and we will again. We can take inspiration from a long history of directly confronting white supremacists, and act in solidarity with the fierceness of Indigenous, Black, and racialized people’s ongoing resistance. If we choose to accept the task, we can be part of an international struggle against authoritarianism, recognizing the ways this ideology traverses (and enforces) borders in its attempts to mold the world in its shape. And we can be part of an intergenerational struggle against authoritarianism, taking up the gift that our ancestors in the movement passed on to us – the dignity of fighting for collective liberation and joy.

If there isn’t currently a convoy in your town for you to fight, you might be following things happening in other places and having many opinions about how we could be doing it better. We know the feeling! To you, we offer the insight that we’ve been sitting with here: Despite doing what we could to build collective movements here in Ottawa, we were not prepared to mount a spirited anti-authoritarian collective response to the convoy arriving and putting down roots in our town. Wherever you are, and whatever tactics you think we should be adopting, the best way to demonstrate that they’re good approaches is to put them into practice: What can you build right now so that you’re ready for the arrival of the diesel-guzzling honkfest in your town?

For us, we’re looking forward to coming together with other like-minded groups to not only push back against the current occupation in a variety of ways, but to also prepare for future confrontations like this. We only call for things that we’re prepared to do ourselves; we’re downright excited to build a meaningful, long-term relationships here in Ottawa so that we can better contribute to the long fight against the right. We hope you are too.

1. Event Description and Details

1. Event Description and Details

This year Punch Up Collective hosted our seventh contribution to recognizing May Day in Ottawa: a kid-centred picnic and short march. We wanted to share something about why this was so fun and to reflect a little on including kids and families in these kinds of celebrations, and the difference between including them and focusing events on kids and families.

This year Punch Up Collective hosted our seventh contribution to recognizing May Day in Ottawa: a kid-centred picnic and short march. We wanted to share something about why this was so fun and to reflect a little on including kids and families in these kinds of celebrations, and the difference between including them and focusing events on kids and families. mal collective might look at this litany and decide that there just isn’t the need in the local radical left to have formal kid care available at our events generally and May Day in particular. 2020’s May Day was the first one under the shadow of the pandemic, and we instead doubled down on trying to do something with kids in mind: we paid a local artist friend to make

mal collective might look at this litany and decide that there just isn’t the need in the local radical left to have formal kid care available at our events generally and May Day in particular. 2020’s May Day was the first one under the shadow of the pandemic, and we instead doubled down on trying to do something with kids in mind: we paid a local artist friend to make

music to tell him maybe not to come. Luckily, he was biking over with his guitar, and so he missed our call, and thus was there when, bit by bit, a whole bunch of adults and kids showed up. Some people knew one another, many others didn’t know anyone. The kids got right down to work making drums out of buckets, shakers out of paper plates taped together with beans and grains inside, and decorating other noisemakers. Others drifted over to draw flowers, hearts, and other more mysterious things on our “Everything for Everyone” banner. People had snacks, and listened to a reading of

music to tell him maybe not to come. Luckily, he was biking over with his guitar, and so he missed our call, and thus was there when, bit by bit, a whole bunch of adults and kids showed up. Some people knew one another, many others didn’t know anyone. The kids got right down to work making drums out of buckets, shakers out of paper plates taped together with beans and grains inside, and decorating other noisemakers. Others drifted over to draw flowers, hearts, and other more mysterious things on our “Everything for Everyone” banner. People had snacks, and listened to a reading of  Although we’d invited people who aren’t parents or caregivers, mostly the people who came were pretty directly connected to the kids there in one way or another. Even though we reached out to parents we know, we didn’t connect with organizers in town like the folks working with Child Care Now, who are campaigning for universal publicly-funded childcare, nor did we reach out to our anarchist librarian friends who host kid-centred events in public spaces in Ottawa to see if they had ideas for activities leading up to the parade that might have brought in people we didn’t already know. In general, we were not thinking sufficiently strategically about the context in which we wanted to participate.

Although we’d invited people who aren’t parents or caregivers, mostly the people who came were pretty directly connected to the kids there in one way or another. Even though we reached out to parents we know, we didn’t connect with organizers in town like the folks working with Child Care Now, who are campaigning for universal publicly-funded childcare, nor did we reach out to our anarchist librarian friends who host kid-centred events in public spaces in Ottawa to see if they had ideas for activities leading up to the parade that might have brought in people we didn’t already know. In general, we were not thinking sufficiently strategically about the context in which we wanted to participate.